| HOME | PRESENTACIÓN | ¿FILMAR LA HISTORIA? | DIRECCIÓN-REDACCIÓN | NÚMEROS PUBLICADOS | NORMAS DE PUBLICACIÓN | CONTACTOS | ENLACES |

|

ROMANCING THE IMMIGRANT IN SPANISH CINEMA: Novelando la figura del inmigrante en el cine español: Lcda. Amy Dolin Oliver

Recibido el 16 de Marzo de 2011 Abstract. The social construction of hierarchies is a method by which dominant groups control the perceived threat of minority cultures. These constructions are only eliminated when those from other cultures are accepted as individuals and equal to oneself. Using relationships as a litmus test for social acceptance, this paper explores the way Spanish national films imagine immigrants and Spaniards in intimate relationships. Over thirty films are studied for their focus on the structural equality present in representations of love, attraction and lust, and prostitution. Analysis of these images provides insight on the circular and metamorphous link between society, the arts, and identity. Resumen. La construcción social de jerarquías es el método a través del cual los grupos dominantes controlan la manera de percibir a las minorías culturales. Tales construcciones solamente son eliminadas cuando los miembros de otras culturas son aceptados como individuos iguales a uno mismo. Usando las relaciones personales como prueba de fuego para la aceptación social, este trabajo explora la forma en la que las películas españolas imaginan a inmigrantes y españoles en relaciones intimas. Más de treinta películas son estudiadas, fijando la atención en la igualdad estructural presente en las representaciones del amor, la atracción y la lujuria; y la prostitución. El análisis de estas imágenes nos proporciona una visión circular y simbiótica entre la sociedad, las artes y la identidad.

From the busy city streets of Barcelona to rural farming towns on the Andalusian coast, foreign-born citizens and native Spaniards are sharing spaces both on and off screen. The tides of migration, once characterized by high outward flow from Spain, reversed direction to provide a swelling immigrant population by the late 1990s. Since this time, migration to Spain has steadily increased giving Manuel Fraga’s claim that Spain is Different a whole new meaning. Current estimates for 2011 put immigration at 12.2% of the total population (INE 2011). Of this total, the most numerous nationalities are Rumanians, Moroccans, British and Ecuadorians. These totals are in addition to the foreign-born population that has converted to Spanish nationality, migrants not legally registered in Spain, and the emergence of second and third generation children of migrant heritage. However different Spain may be from an imagined homogeneous past, increased immigration has made it less different from other European countries that have adapted to similar demographic changes in previous decades. Close proximity of different cultures can produce friction and xenophobic reactions as well as lead to friendships, love and cultural crossings. For Zygmunt Bauman, both of these responses are tied to desires to control the perceived threat of strangers. He bases his hypothesis on the writings of Claude Levi-Strauss whereby primitive societies dealt with strangers and their perceived dangers by eating them up and digesting them while modern societies expel and exile strangers (Bauman, 1993: 163). Bauman, however, believes modern societies currently use both of these concepts: “The first ‘assimilates’ the strangers to the neighbours, the second merges them with the aliens. Together, they polarize the strangers and attempt to clear up the most vexing and disturbing middle-ground between the neighbourhood and alienness poles”. Yosefa Loshitzy ties these strategies to the processes Fortress Europe uses to maintain European culture, identity, benefits and privileges that are denied to those screened out (Loshitzky, 2010: 3). The process of assimilating and expelling strangers is connected to the construction of social hierarchies. All societies hierarchize cultures different from their own, which are invariably considered inferior, state sociologists Berger and Luckmann (Berger and Luckman, 1986: 132, 136). These techniques are not unique to Spain nor even to the modern world. Herodotus said in 450 B.C., “Everyone without exception believes his own native customs, and the religion he was brought up in, to be the best” (Herodutus, 1996: 3.38). In globalized environments, it is increasingly common to have multiple distinct cultures living in the same national boundaries. The dominant population or culture stratifies the less populous cultures into sub-hierarchies with varying levels of acceptance in an attempt for control (Todorov, 1989: 118). Some cultures are more accepted while others experience higher levels of xenophobic rejection. The study of hierarchies in relationships, or lack of them, can reveal the social structure in use by dominant societies or cultures. Film is a medium that functions both as an art form and a source of entertainment while documenting views and manners of acceptable behaviour at specific historic times and geographical locations. It is a social instrument with enormous repercussion able to reach large and diverse audiences. In large part it feeds off of the same stereotypes circulated in and generated by the public consciousness. Fear of other cultures and nostalgia and a sense of loss for self-created myths of homogeneity find their way into film representations. Various approaches reproduced in film stimulate equality in the power structure and set aside hierarchy constructions or serve to reinforce these. As shown by Edward Said, images created of other cultures do not reflect these cultures but instead what the author and his or her society attribute to that culture. “I believe it needs to be made clear about cultural discourse and exchange within a culture that what is commonly circulated by it is not “truth” but representations” (Said, 1978: 21). Often the Other is reduced to stereotypes and reproductions of inferiority. These make use of the same imagery as has historically been used on repressed groups such as woman, children and the domesticated animal (Perceval, 1995: 43-51). Use of the immigrant as a fetishized or exoticized object is one such manifestation of subordination in the hierarchy. Film has become one of the principal players documenting Spain’s artistic coming to terms with encounters with people of different cultures. A great part of Spanish film, during its history has portrayed the phenomenon of social and migratory movements (rural exodus after the civil war in the late 1930’s, ensuing massive emigration to richer countries of Europe, and the recent immigration of Africans, Asians, Latin-Americans, etc). Therefore, since the 1990’s, contemporary Spanish film has evolved into a qualified witness of immigration, whose filmic representation has grown in the last years on par with its repercussion at all levels of Spanish society and in the media. There are well over one hundred full-length Spanish films produced whose representations create a visual documentation highlighting immigration. These films debate the construction and transformation of immigrant acceptance as well as accentuate xenophobic hierarchization. In particular this paper aims to analyse inter-ethnic images of matrimony, coexistences and hybrid relationships as shown on the big screen. This theme takes on special resonance as matrimonies, coexistences and hybrid relationships are taking place between Spaniards and immigrants all the time. Different from reality, the filmic versions are created through artistic imagination and consciously and unconsciously reproduce the dominant ideologies prevalent in a particular time and space. Studying these representations provide awareness of levels of equality and/or hierarchy towards the migrant as they are filtered through representations of love and baser desires. The films examined include representation of intimate relationships between Spaniards and migrants from economically less favoured countries. The vast majority of these films were created by the dominant population. A small quantity of films were directed through co productions and are highlighted when present. After sorting through the representations of crushes, commitments, prostitution, one-night stands involving a foreigner, a number of repeating categories began to emerge. These were divided into three groups: love, attraction and lust, and prostitution. Films are discussed in a historical chronology inside of these three categories to better highlight the progression of social changes. The relationships portrayed can be seen to evolve over time with the maturing of the dominant and migrant populations. In examining these relationships and the hierarchies they imply, this paper uses themes from identity, alterity and image representation to reflect on the following questions: Are social hierarchies set aside in film when the Other is accepted as a partner, and, Are hierarchies firmly in place when it comes to lust and prostitution? Love: An Evolution from Rocky to Stable Relationships From the 1970’s and on through the 1990’s Spain first began to attract immigration of wealthier citizens from Northern Europe and the United Kingdom in particular. Alarm over immigration, however, did not become a public concern until immigrants from poorer countries began to arrive in the late 1980’s drawn by the growing industrial and agricultural economic impulse of a Spain newly emerged from a dictatorship. The majority of these immigrants were young men quickly absorbed into construction and agricultural positions. In 1996, Spain’s immigrant population still remained one of the lowest in all of Europe at a little over 1% of the Spanish populace. Even so, concern over immigration was one of the top five preoccupations of the Spanish people. In large part this fear was a direct consequence of disproportionately heightened media coverage on migrations (Granados, 2001: 3). Cinematic coverage of immigration is often signalled at starting in 1990. However as early as 1975 immigration themes began to appear in Spanish cinema. Right from the outset these films included interracial relationships as plot story lines. This extended to all levels of character development: protagonist, secondary actors and background characters. In the earliest films, although mixed relationships were typical plot functions (Flesler, 2004: 106), interracial relationships were treated warily. Nevertheless these early films brought attention to social injustice, introduced the intimacy possible in mixed relationships, and laid the groundwork for ensuing films. During the 1990’s and early 2000’s, Spanish social reaction to migration was to merge the immigrant with the stranger and alien. National films embraced a structural pattern in which the immigrant male (whether Senegalese, Moroccan, Indian, Eastern European or Russian) was permitted to love but not marry or continue a long-term relationship with a Spaniard. More often than not, these relationships ended with the death or disappearance of one of the partners. Frequently this happened at the crucial point when the relationship was about to transition to a more mature level. Immigration was still a new concept, and the Spanish population was only beginning to grasp the reality that their country was now attracting and needing immigration. The idea of relationships involving a foreign male seemed to strike a primitive need to protect or dissuade females from separating from the pack which manifested itself in film.

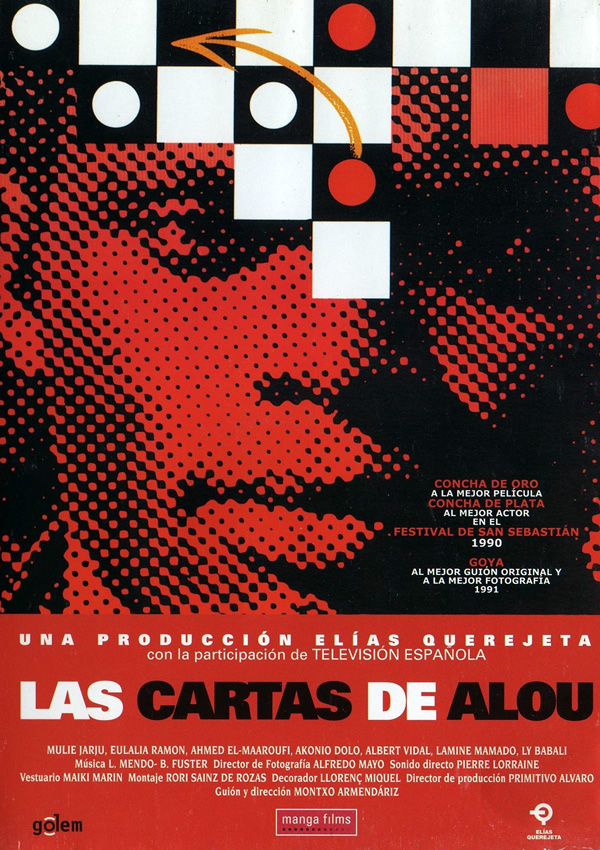

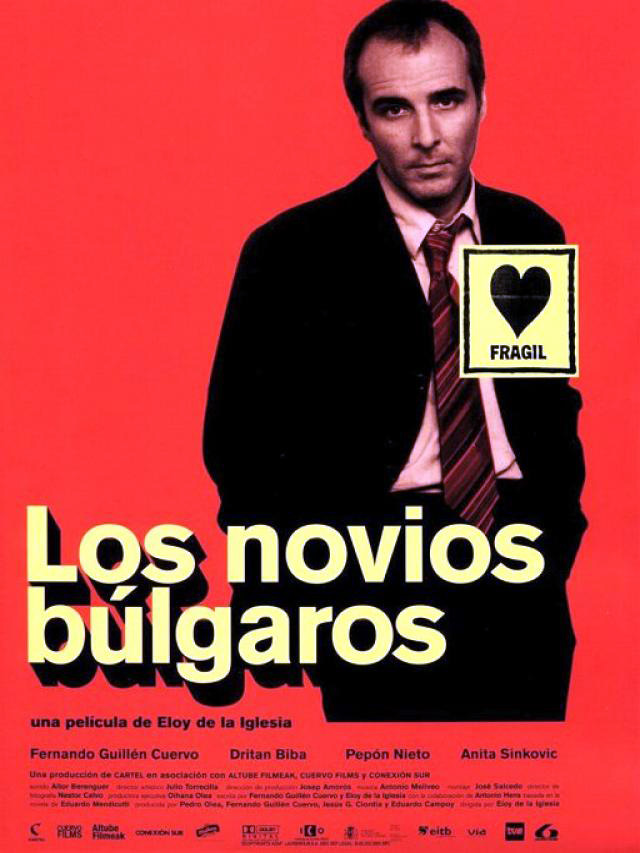

On screen killing or deporting of male immigrants and thus cross-cultural relationships was a symbolic way to eliminate a threat to social hegemony. Such was the case in the film Las cartas de Alou (Letters from Alou- 1990, Montxo Armendáriz) in which Alou, a Senegalese migrant, is deported just when he and his Spanish love interest, Carmen, are about to move to a more public stage in their relationship (Flesler 2004: 107, Molina Gavilan and Di Salvo, 2001: 3). For Niña, in Hola ¿Estás sola? (Hi, Are You Alone?- 1995, Icíar Bollaín), after falling in love with a Russian, Olaf, she and the viewer are left wondering at his disappearance just after she has invited him to come work with her for the summer at her mother’s beach bar. In Saïd (1999, Llorenç Soler), the Moroccan title character is attacked by racists while walking down the street with his Spanish girlfriend, Ana. He is next arrested by the police and faces deportation. More tragically, in Susanna (1996, Antonio Chavarrías) the punishment for being engaged and attracted to a Moroccan man results in death. The marriage between Susanna and Said, a Moroccan butcher, never takes place as she is killed by her jealous Spanish lover and Said is framed for the murder. Isabel Santaolalla and Daniel Flesler trace many of these failed romance attempts to the Muslim heritage of the male immigrants portrayed. Santaolalla cites Saïd and El Faro (The Lighthouse- 1998, Manuel Balaguer) as two examples of films in which mixed relationships with Maghrebi men are truncated probably due to a long tradition of interracial relationships not functioning (Santaolalla, 2005: 136). Flesler makes the case that films which highlight the differences of Muslim men, “clearly blame them and their alignment with their ‘cultural traditions’ for the failure of the romance”, citing these as doomed by Spaniards as an identity conflict (Flesler, 2004: 112-113). She adds to the list Tomándote (Two for Tea- 2000, Isabel Gardela), where open and sexually experimental Gabi falls in love with a semi-traditional Muslim Jalil. In addition to Muslim men, the immigrant male in general remained depicted as an inadvisable partner as seen by another film of the same year, Leo (2000, José Luis Borau), in which Gabo, an Eastern European, is shown to have been in unsettling sexual circumstances with the daughter of his ex-partner. This also applies in the later film Los novios búlgaros (Bulgarian Lovers- 2002, Eloy de la Iglesia) in which Daniel falls in love with Kyril, a Bulgarian immigrant, although well aware that Kyril is using him for financial interests and disappears when Daniel is no longer useful to him. Daniel, by falling in love with an immigrant becomes vulnerable and feminised in comparison with Kyril. One exception during this time period is the background character Mulai in Las Cartas de Alou. He is a childhood friend of Alou living in Barcelona and married to a Spanish woman with whom he has a child. He is shown to be prospering both economically and in love. However his economic success is shown to come from exploitation of his countrymen and therefore he is not viewed as an exemplary character. Female immigrants found a much more accommodating treatment in Spanish film than their male counterparts. While the migrant male was represented as a threat, migrant females were overwhelmingly shown as beautiful women in dire need of arranged marriages. As more women began to migrate to Spain their presence in filmic relationships with Spaniards increased. As early as 1975, the destape film Zorrita Martinez (1975, Vicente Escrivá) introduced Lydia Martínez, a Venezuelan cabaret dancer with the stage name Zorrita, who convinces the much older Spaniard Serafín to marry her so that she can stay in Spain. Almost twenty years later, the arrival of three Cuban sisters, Rosa, Lumilda and Nena, in Cosas que deje en La Habana (Things I Left in Havana-1997, Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón) marked the beginning of the next series of films documenting alliances between Spanish males and the female immigrant. Like Zorrita Martinez, it also centres on an opportunistic marriage for papers. Lumilda accepts Javier, a homosexual man, as her groom and in the process doubts are raised whether Javier is homosexual or merely inexperienced. The relationship is not based on equality but instead a hierarchy system where an inexperienced Spaniard dominated by his mother is paired with an attractive female immigrant. It also continued to reinforce the failure of relationships with foreign males. Igor, a Cuban who deals in contraband Spanish passports, advances himself by seducing the Spaniard Azucena to support him. By the films end this relationship has ended, and Igor’s future is pessimistic.

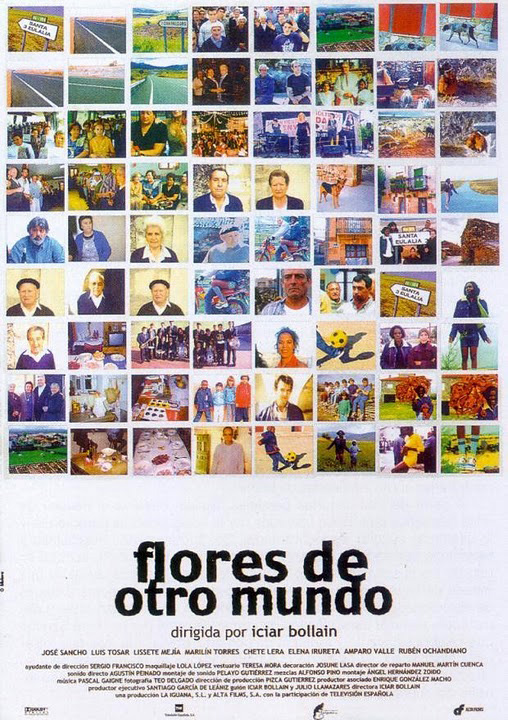

Also depicting this theme of marriages based on alliances is the relationship between Patricia and Damian in Flores de otro mundo (Flowers from Another World- 1999, Icíar Bollaín). Damian, like Javier, is shy, obedient to his mother, and ready to marry. Similar to Lumilda, Patricia is Latina (Dominican), attractive and looking for legal papers. In this union Patricia sees a way to stop a clandestine existence in Spain and to bring her children overseas. Damian in turn wants to stay in his home village, a village in need of saving from total extinction (Santaolalla, 2005: 195). Patricia and Damian find love, treating each other as equals although they remain subjected to existent male-female hierarchies. A second unsuccessful relationship highlighted in the film is that of Milady, a young Cuban, and Carmelo, an older construction manager who has brought her to Spain. Their relationship is based on Carmelo’s sexual interest in her and Milady’s desire to be in Europe. The failure of this relationship is marked by intense inequality in Carmelo’s patronizing and chauvinist treatment of Milady and her lack of interest in what Carmelo has to offer now that she is in Europe. The film La fuente amarilla (The Yellow Fountain- 1999, Miguel Santesmases), provides an exception. The protagonist, Lola is a second-generation child of mixed heritage, and therefore both insider and outsider. She is not in need of papers as she is already Spanish, instead she is in need of vengeance. After avenging the murder of her Spanish father and Chinese mother, Lola witnesses her new love Sergio killed by gunfire. Just prior to his death they had agreed to begin a serious relationship together. Not only does Sergio die, but everyone she has loved: her parents, her first boyfriend and a Chinese cousin she has been intimate with, all end in gun inflicted deaths. She fits the archetype of the tragic mulatto whose loves end in death. Treatment of Lola is similar to the formula used for male immigrants in film, that of elimination on the verge of love culmination. The turn of the century witnessed increases in migration to Spain. The Spanish government processed three new rounds of regularization to legalize immigrants working in Spain (2000, 2001, 2005). The country was experiencing an economic boom and needed workers. By 2007, conservative statistics estimated immigration in Spain at approximately 10% of the population, 4.5 million out of the 44 million residents in (INE 2007). Filmmakers gradually projected more favourable images of Spaniards pairing with individuals from foreign cultures. This evolution of themes echoed reality, where mixed marriages, between Spaniards and foreigners rose from 4% in 1996 to 10.7% in 2005 (Morán, 2007: 40). The premise of impossible love began transforming as Spanish films acknowledged the robust complexity of the lives, livelihoods and countries of immigrants. Such was the case in the film A mi madre le gustan las mujeres (My Mother Likes Women- 2001, Daniela Féjerman, Inés París), which took the Spanish viewer to Czech and the immigrant country suddenly had a voice and images. In this film, Sofia, a successful Spanish pianist falls in love with Eliska a younger Czech woman. The balance of power tips strongly towards Sofia, as she is much older, much richer, and more successful as well as being Spanish with no visa problems. However, Eliska retains her autonomy and therefore her equality because she is not trapped in Spain. When persecuted by Sofia’s children she leaves Sofia and returns to the Czech Republic. She is again reunited in love with Sofia by the end of the film. Similarly, in I love you baby (2001, Alfonso Albacete and David Menkes) the theme of impossible love lost and recovered continued as Spanish Marcos, after experimenting with a relationship with another man, Daniel, falls in love with Marisol, a Dominican. The film alternates between scenes focusing on Marcos and Daniel’s lives and of Marisol and the lives of other immigrants in Madrid, offering a glimpse into life from a migrant’s point of view. However, the most dramatic changes in representation of love relationships occurred in the representation of immigrant male characters in love relationships from 2003 on. Background character roles, such as in the film Ilegal (2003, Ignacio Vilar), while denouncing immigration mafia networks, began to show Spanish women with Moroccan boyfriends/husbands in stable relationships. Nonetheless the single biggest factor to influence changes in the fortune of foreign men and love relationships with Spaniards was the increase of immigrant male secondary characters used in comedies. The narrative structure of a comedy often ends with a happy ending. In romantic comedies this permitted a happy romantic ending for both Spanish and culturally mixed couples. These initial inroads allowed by comedies allowed inclusion of male immigrants in long-term relationships however they continued to not be accepted as equals nor involved in healthy relationships. Such is the case for Cosas que hacen que la vida valga la pena (Things That Make Life Worth Living- 2004, Manuel Gómez Pereira) which introduces as a side plot Chen, a Chinese man married to the Spaniard Angeles. Chen provides a double reading of the male immigrant in relationships. He is portrayed as married to a Spanish woman as well as very involved in the life of her child from a previous marriage. Despite these positive accomplishments, he is used for comic exotic effect, presented as feminised in comparison to Spanish males, and as tolerated instead of loved by Angeles.

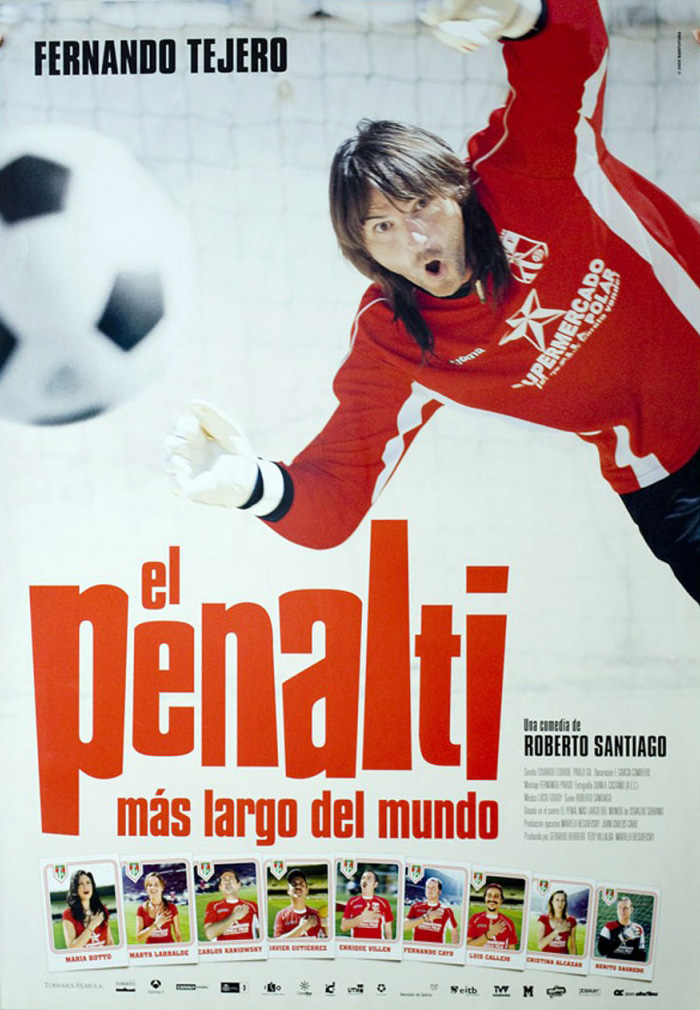

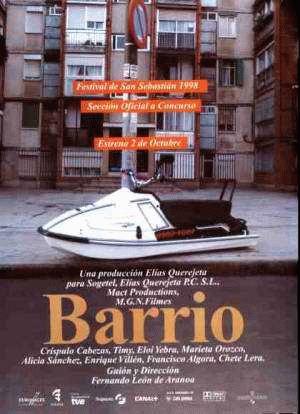

With the increase of immigrant characters in comedies, immigrant men began to be portrayed in films with healthy love endings. One of the earliest films to show a successful relationship forged between the immigrant man and the Spanish woman is El penalti más largo del mundo (The Longest Penalty Shot in the World-2005, Roberto Santiago). In this story, the Spaniard Ana breaks up with Khaled, her Moroccan boyfriend, after tiring of a relationship that she feels has no future. By the films end he wins Ana back and they have plans to move in together. Khaled is depicted as integrated in the Spanish community. He is both feminised and masculinised regarding stereotypical male and female attributes. This film is the first to positively develop a forward reaching love relationship between a Spanish woman and Moroccan male in more developed character roles. Later films such as Fuera de Carta (Chef’s Special- 2008, Nacho G. Velilla) further extend this pattern. In this film the Spanish chef, Maxi, and the ex professional Argentinean Soccer player Horacio find their way to love and societal acceptance of this love by the community and their families. Representations of relationships with immigrant females, continued to have high chances for success. They also increasingly moved towards being represented the similarly to Spanish women, as equals in society. The majority of these relationships involved Latin American women. One such example is that of Elsa y Fred (2006, Marcos Carnevale), directed by an Argentinean director, in which Argentinean Elsa finds love later in life with Spanish Fred. Migrants from other countries, although less represented, had equal success rates. Even the Muslim taboo is seen to crumble in the pairing of Bangladeshi Aisha and Spanish Cain in El Próximo Oriente (The Near East- 2006, Fernando Colomo). Aisha is the lover of a married man Abel, who continually promises he will leave his wife for her. When she finds herself pregnant, it is not Abel, but his less attractive brother Cain who helps her through her difficulties. He converts to Islam, integrates himself with the family and marries Aisha. By the end of the film she too has fallen in love with him for his respect towards her and her family. Here again is a version of the bumbling goofy not attractive Spaniard who marries a beautiful immigrant. This time however, it is not so that she can have papers in an arranged marriage, but to save her reputation with her family. Siete mesas de billar francés (Seven Billiard Tables- 2007, Gracia Querejeta) portrays a mixed relationship in which the Spanish male patiently waits for the relationship to enfold. Evelin is a Honduran woman living in Madrid who dates Fele, a painter and billiard player. Both work in the same bar and discreetly are involved in a relationship. They try not to publicize this as Evelin has a husband back home in Honduras. She maintains regular phone calls and sends monthly money to her husband until she discovers that he has no plans to reunite with her and has fallen in love with her sister. Fele and Evelin continue their relationship, now publicly. Evelin and Fele are portrayed as slightly immature characters however their love is one of equals. Similar to Siete mesas de billar francés, the film Pagafantas (Friend Zone- 2009, Borja Cobeaga) includes a Spanish male waiting for a chance at love. However, this story puts a modern twist that reverses the trope of goofy Spaniard and beautiful immigrant who marry for papers. Chema falls in love with the beautiful and fun Argentinean Claudia, however Claudia only sees Chema as her friend. While waiting for Claudia to realize he loves her, he agrees to marry her so that she can stay in the country. Claudia never imagines Chema as someone she would date which is made even more evident when her attractive and successful Argentinean boyfriend returns to Spain to live with her. Chema, even after getting over his love for Claudia is helpless when he is near her. Claudia is not portrayed as helpless, but instead as opportunistic while unaware of the power she holds over Chema. In this film, the migrant female, particularly the Argentinean female, reaches a level of equality in the hierarchy similar to a Spanish woman faced with a weaker Spanish male. One other area that deserves mention is the scarcity of images that represent the children of intercultural pairings. While in Spain, children of mixed marriages reached 11.5% in 2005 (Morán, 2007: 40) only a handful of films portray this. These films include I love you baby in which by the end of the film Marcos and Marisol are shown five years later, with Marisol’s daughter from a previous partner along with two children they have had together and fourth child they are expecting. Other exceptions in films previously noted are Las cartas de Alou, La fuente amarilla, and El Próximo Oriente. Attraction and Lust: Unequal Pairings The filmic equality growing in love relationships is in marked difference to that shown in relationships between the Spaniard and immigrant based on attraction or sexual interest. The representations are almost entirely of background characters. Scenes of attraction are above all involving the Spanish male towards the female immigrant. Surprisingly, the majority of lust encounters are initiated by Spanish women. A small sample of films touch on the attraction felt by Spaniards towards immigrant females without the story going beyond. These feelings tend to be harboured by powerless young Spaniards attracted to female immigrants as part of the young men’s sexual initiation. Such is the case with teenage Manu in Barrio (Neighbourhood- 1998, Fernando León de Aranoa), who observes from afar a Dominican babysitter who sits at the park, or with Epo who flirts with a much older Argentinean shopper in Tapas (2005, José Corbacho and Juan Cruz). In Torrente (1998, Santiago Segura) awkward and nerdy Rafi, sidekick to the protagonist Torrente, finishes the film with his arm around a young Chinese waitress who has saved his life. Similarly following this pattern, Elvira, the youngest daughter of Sofia in A mi madre le gustan las mujeres kisses her mother’s Czech lover to test her own sexual orientation. When the immigrant male acts on his attraction, he tends to be of a lower social class level than the Spanish female and the results end in failure. This highlights the double hierarchy of class and Other status. Such are the cases of El traje (The Suit- 2002, Alberto Rodríguez) and Animales heridos (Wounded Animals- 2005, Ventura Pons). In El Traje Patricio, an African immigrant, through the confidence and respect gained by a suit given to him, arranges a date with a Spanish shop assistant. She remains interested in him until she sees that he isn’t all the suit promises and hasn’t been truthful to her. In Animales heridos Jorge Washington, a Mexican handy man and boyfriend of a Peruvian housecleaner, flirts with the wealthy female Spaniard whose house he is painting and later wistfully holds the water bottle of another wealthy Spanish woman whom he doesn’t have the courage to approach.

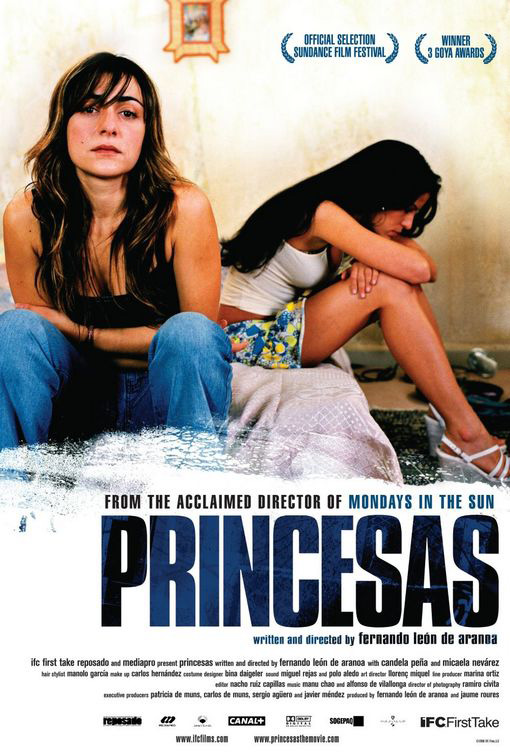

Immigrant males also emerged as the object of Spanish female desires. These relationships, initiated by Spanish women represent part of the new status of women portrayed as sexually equal and dominant in amorous relations. They also highlight the shifting power hierarchy of the immigrant as subordinate to the Spanish women. A collection of films shows the immigrant male as an exotic or taboo desire. In Las Cartas de Alou the women who take Alou and his friend home for a one-night stand sneak them into the building to avoid their neighbours. More tragically, after the fetishized sexual fantasizing of a Spanish housewife in Bwana (1996, Imanol Uribe) for the African title character of the film, Bwana meets a violent death. Other images represent the Spaniard looking for opportunity from unequal immigrant character positions. These story lines often present large age differences between an immigrant male and a Spanish female. Such is the case of aging América with her young black lover in Cosas que hacen que la vida valga la pena and the underage Estíbaliz with Mexican Waldo/Osvaldo a maintenance man at a hotel in Atasco en el Nacional (Traffic Jam on the National- 2007, Josetxo San Mateo) whom she mocks for the size of his sexual organs. However they also apply in the treatment of male immigrants by Spanish males such as in the film Los novios búlgaros. Both Daniel and his friend Gildo enjoy the company of much younger Bulgarian boys. Gildo likes the playful distraction of the foreign boys whom he treats similar to lap dogs, or as exotic animals. Gildo’s relationships are marked by sexual interest and complete inferiority of the immigrant. Prostitution - The Overrepresented Occupation The lowest of the hierarchy groupings is that of the immigrant portrayed in the sex trade. In a study on Spanish film of the 1990’s, Pilar Aguilar Carrasco states that the most frequent occupation for non-protagonist role females, both Spaniard and immigrant, was that of prostitute or sex club workers (Aguilar Carrasco, 2006: internet). By 2007, this category was the most frequent way in which a relationship between a Spaniard male and migrant female was represented. A few of these films gave voice to the female immigrant prostitute in protagonist roles. Much more common were brief scenes involving the main or secondary characters patronizing an immigrant prostitute as background characters. As a whole, immigrants from Latin countries received the majority of attention with Russians being the second most represented. The Latin prostitutes hailed from the Dominican Republic, Uruguay, Brazil and Venezuela and were generally represented as highly attractive. An in-depth study by Isabel Argote of all films opened in Spain during the period of 2000 to 2002 showed that the female immigrant was most frequently portrayed as a prostitute (Argote, 2003). During this three-year period she details an extensive list of films that portray Latin American immigrants in roles of prostitution or exchanges for sexual services generally in background scenes. Amongst others she includes, Pídele cuentas al rey (Asking for an Explanation from the King- 1999, José Antonio Quirós) in which a Caribean mulatta and black females work at a sex club and Piedras (Stones-2002, Ramón Salazar) which depicts South American women prostituting on a street corner. Later films continue to reproduce this theme. One such film is Un rey en La Habana (A King in Havana- 2005, Alexis Valdés), which comically addresses the topic of immigrants and prostitution in the slave trade. After an arranged marriage between the Cuban mulatta Yoli and an older Spanish man disintegrates upon the death of the groom, it comes to light that he had intended all along to kidnap her through a false marriage to send her to work as a prostitute in Spain. Alternately, La torre de Susa (2008, Tomás Fernández) touches on the relationship between one of the secondary characters and his Dominican girlfriend who works as a prostitute in the village. Not all films portraying the immigrant as sex worker are limited to background roles. Three films showing immigrant prostitutes in protagonist or supporting actress roles are En la puta vida (In This Tricky Life- 2001, Beatriz Flores Silva), Princesas (2005, Fernando León de Aranoa), and Desde que amanece apetece (From the Moment You Wake, You Want It- 2006, Antonio del Real). In strangely similar circumstances, the immigrant women depicted are all originally from Latin American countries, supporting a child back home, and by the films end return to their native country through the help of a Spaniard. These films tend to show the immigrant in disadvantaged equality with their partners or clients.

En la puta vida is unique in the films depicting prostitution in that it is directed by a Uruguayan director in a Spanish/Uruguayan co-production. The film presents Elisa, a prostitute who emigrates from Uruguay with her pimp boyfriend. When things do not go as expected there, a Spanish policeman, Marcelo, helps arrange for her to return home to her children. The film ends with both hope and uncertainty as to her future; the last scene shows a budding relationship with Marcelo yet the text in the credits casts doubt on her future safety in Uruguay. In Princesas, Caye, a Spaniard, and Zulema, a Dominican, work as prostitutes in Madrid. Many of the street scenes contain representations of Latin and black prostitutes who are viewed as competition by the Spanish prostitutes. Zulema sends money to her family and little boy back home. She is stalked and abused by one of her clients and earns less money than the Spanish prostitutes. At the films end Caye and Zulema have developed a friendship, and Caye pays for Zulema’s flight home. In the comic film, Desde que amenece apetece, Pelayo falls in love with Claudia, a Venezuelan prostitute considered the best of the brothel for her energy in bed. Pelayo helps Claudia return to her country and young son with money he has inherited through his own sexual services as a gigolo. The frequent representation of Latin Americans as prostitutes in film is in part a reference to the increase of these nationalities in the Spanish population and their statistical presence in prostitution (Agustin 553). However these depictions are also a way to inferiorise the subset of the immigrant population that has the greatest ability to insert itself into the Spanish society due to lack of language barrier, past colonial connections, and ease of converting to Spanish nationality. If Spanish film provided a faithful portrayal of the Latin American immigrant population in Spain, we would expect to see a much larger representation of the immigrant female working in hotels and restaurants, as caregivers to the elderly and children, or as housekeepers, where a great majority of this population actually find employment (Argote, 2003: 6).

However, prostitution is not limited to female migrants. Though less frequently, there are also representations of immigrant male prostitutes. Two such example films that are Desde que amanece apetece in which male strippers from Brazil, Africa, Russia and Cuba work and the Bulgarian boys in Los novios búlgaros. These films tend to represent the male prostitutes as having fun with rich clients and entering in prostitution as an enjoyable way to of prospering financially. This candified treatment of prostitution is similar to the representation of Spanish female prostitutes in the films here examined. For example Caye in Princesas works to earn money for a breast enlargement while the Spanish prostitute in Un rey en La Habana works because she enjoys relieving men’s stress in sadomasochistic games. Conclusions As can be seen from this analysis, a sharp difference exists in the treatment of the immigrant in love relationships as compared to other sexualised roles. In films where the immigrant is accepted as a love partner, social hierarchies are evolving towards acceptance and equality. For the immigrant male this transition has been quite dramatic as early films truncated future relationship possibilities with Spanish women. This was the case for most relationships with immigrant males, in films up through 2003. More recent films have started to allow positive relationships with Spaniards, loosening hierarchy treatment. From 2004 through 2009 there is a marked change for the positive in the acceptance and integration of the male immigrant as a love interest. The female immigrant, on the other hand, has almost always been accepted in love relationships, where fears over interracial mixing dissolve. This is in a sense a repetition of unions produced during the Spanish colonial empire in which male Spaniards freely intermarried with local women. Relationships with female migrants are shown to flourish and often lead to marriage. While a large number of these relationships unite a highly attractive female immigrant with a less advantaged Spaniard (either physically, socially or age-wise), over the course of the past two decades there has been a steady increase towards equality in the treatment of the female immigrant. Hierarchies are firmly in place when it comes to lust and prostitution. In the category of attraction and lust, the degree of equality plummets as most advances are made by powerless younger Spaniards initiating themselves in courtship rituals by practicing on attractive immigrant females, by powerless male immigrants towards more successful Spanish women and by sexually interested Spanish females often with large age differences preying on migrant men. Films that depict the female prostitute as part of background scenery demonstrate the lowest level on the hierarchical scale involving the immigrant in relationships and also make up the highest total of representations. These films do not provide more than glimpses of the immigrant working in degrading surroundings and with characters representing the bottom echelon of Spanish society. Portrayals of the immigrant prostitute in protagonist roles and secondary roles centre on their desperate economic need and lack of alternatives. Often the women are required to send money home to family or children in their original country and return to their home country by the end of the film. These personalities are given voice but not treated as equals, and receive a different treatment as compared with the Spanish female prostitute and the male immigrant prostitute. In one sense Bauman’s theories can be applied to these results. On the one hand, a move towards assimilating the immigrant stranger is seen in the increasing number of films portraying successful long term mixed culture relationships taking place in comedic films in current Spanish cinema. On the other hand the elimination of immigrant males in love relationships in the early films and the high proportion of current films which portray immigrant females as prostitutes maintain a strong alien sentiment towards the immigrant and non-acceptance as equals in the social hierarchy. With regards to specific immigrant cultures, Latin Americans, with the exception of Argentines, are treated very ambivalently- appearing most frequently as equals in love relationships as well as in prostitution roles. Argentines are most likely to be portrayed as equal to Spaniards. Muslim and Moroccan men also receive a heightened percentage of representation with representation changing from non-acceptance to limited successes. Romanians and Ecuadorians, two of the top five populations in Spain, receive scarce to null representation. Analysis of these films provides insight on where Spanish artists are positioning the immigrant Other in their vision of society. Nonetheless, statistical information on percentages of mixed marriages, birth rates of mixed children, and where immigrants are really employed paint a much different story than the filmic representations. However, these films are also crucial in the opening of doors to new acceptance and as a measure of what the society is presently able to conceptualise in the construction of immigrant place and a changing Spanish identity. Works Cited

ISSN 1988-8848

|